13 Ways of Looking: Simon Wu

Stewart Uoo, Untitled (After Hiraku Taku II), 2014.

The first thing I did when I began to think seriously about putting together a book was to call some artists that I had long admired but whose studios I’d never had the chance to visit. One of those artists was Stewart Uoo. Stewart is gentle and very tall, with kind eyes and elegant, long, gray hair—“handsome, if somewhat aloof,” as Andrew Durbin describes him in Macarthur Park (2017). I’d met him here and there at openings and parties, but this time I asked him to give me the full low-down on his work and he kindly agreed. We sat in his Bushwick studio as the sun went from bright yellow to brown honey on an early spring day, and he clicked through image after image of a decade’s worth of artwork, taking detours for gossip, production mishaps, and context. Afterward, we got a drink and then I went home.

I wasn’t entirely sure what he had shown me, but I felt a light buzzing in my chest. I was excited. It all felt relevant. When I say that word I think of revelation––the feeling of new knowledge on the horizon––and also relative––the feeling of connection on a bodily, familial level. Stewart’s work felt relevant to the book I wanted to write, to my life, to my future. But this was all just a feeling. Could I trust it? His work is hard to categorize—across sculpture, photography and drawings—but I began to graft a transformational metanarrative onto it: Stewart took his background as a gay, Korean-American child of immigrants and let it oxidize in the fashiony art world of New York. Lying on my bed, I scrolled through the files he sent me via Google Drive on my phone.

One work in particular stuck with me: Untitled (After Hiraku Taku II) (2014). Initially, I was drawn to the image for the gay mundanity that it portrayed. Two men––lovers––laugh in a kitchen. One of them does the dishes while the other dries them. The man on the left wears white socks; the other is barefoot, and his toes almost lift off of the floormat, even the edge of the watercolor itself, as if his partner’s laughter could levitate him. There is intimacy, but there is also something unresolved: is there insecurity in the way their glances search for one another? “Something about that image contains so many conflicting and harmonious feelings to me,” Stewart said when I asked him about it again, years after our first studio meeting, “It really makes me laugh.”

Untitled (After Hiraku Taku II) is a meticulous re-creation of a scene from a Japanese gay manga by Hiraku Taku that Stewart found on DeviantArt in 2010. He couldn’t remember exactly which one, but it was a digital image that he edited, changing the shirt, adding the crossbody bag. It reminded me of what one might do in grade school, tracing drawings and copying them out of fascination and love. Other works in the Untitled series are more sexually explicit, and Stewart’s hand is more visible: close-ups and watery scenes of bara (Japanese gay porn for men), yaoi (Japanese gay male romance for women), and fisting (self-explanatory). Untitled captures not only the image of gay domesticity but also records Stewart’s admiration for another artist’s work. It is a reproduction that becomes its own rendition; something like a “cover” of another’s song.

The gesture of one artist grasping for another across time and space became an engine for the writing in my book Dancing On My Own. Taking in Stewart’s artwork was one of multiple instances that ushered this powerful feeling of artistic time-travel. At the time I could only identify it by intuition; in retrospect, I understand I had made myself open to something, and when you do that, sometimes the world whispers back to you.

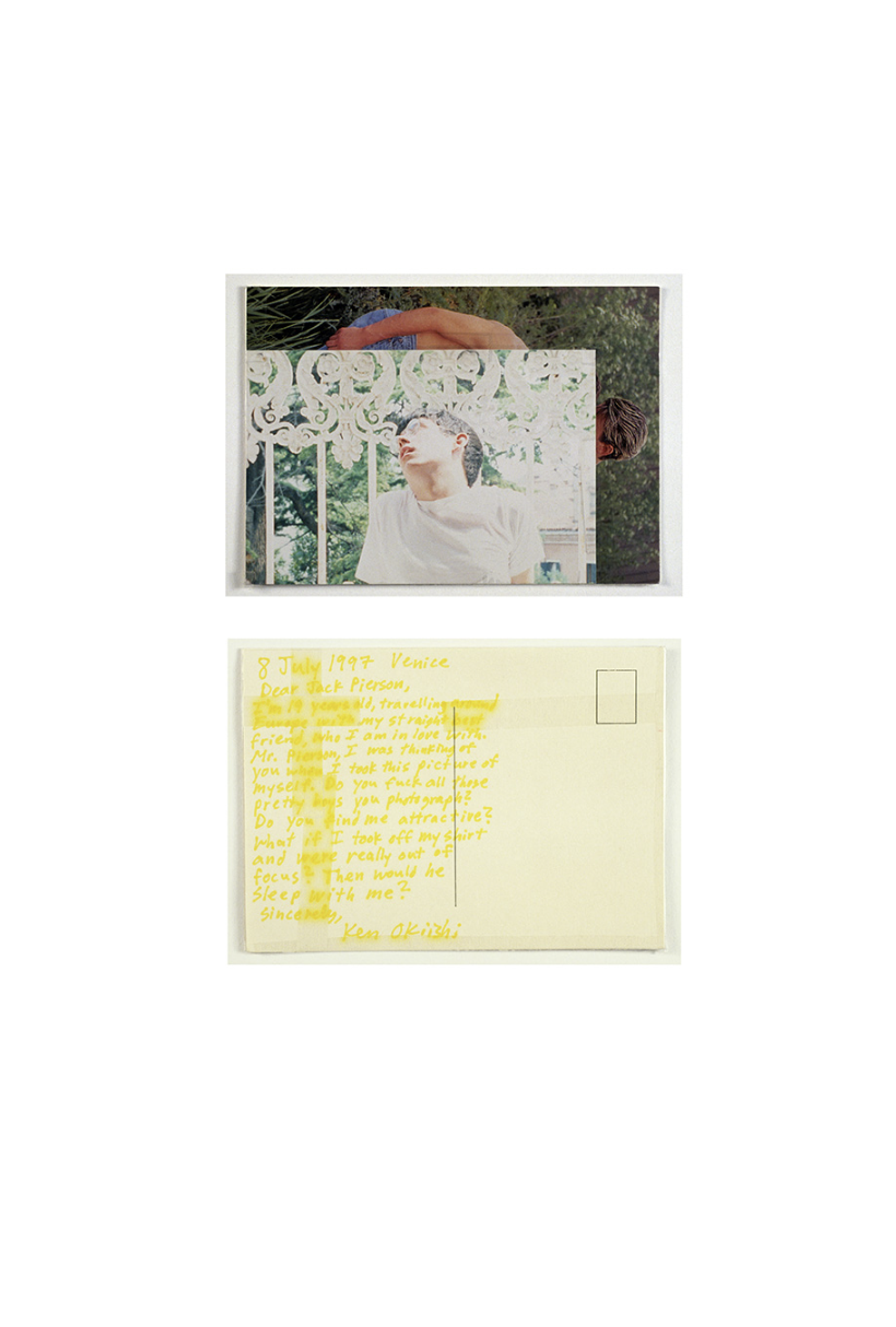

Ken Okiishi, Wish I Were Here, 1997 - 2001.

Another artist on my list was Ken Okiishi—Japanese-American, long-time New Yorker, video artist. I sent him a gushing email requesting to meet up. Thankfully, he was flattered and said yes. We had coffee. He showed me his studio. The next time we met up, he took me on a memory walk to clubs he used to go to. He asked whether this or that person was still famous. I learned about Wish I Were Here (1997-2001), one of the earliest works he made when he was still a student at Cooper Union, Ken writes letters to famous artists like Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, and Jack Pierson about what techniques of theirs he could use to make his straight best friend fall in love with him. The works are simple: two pictures, usually one of Ken in the style of the artist, the other of a beautiful boy, interposed on one another, with a postcard letter below. The title Wish I Were Here captures this wistful, yearning gaze, taking in another artist’s practice, as well as the gulf between them.

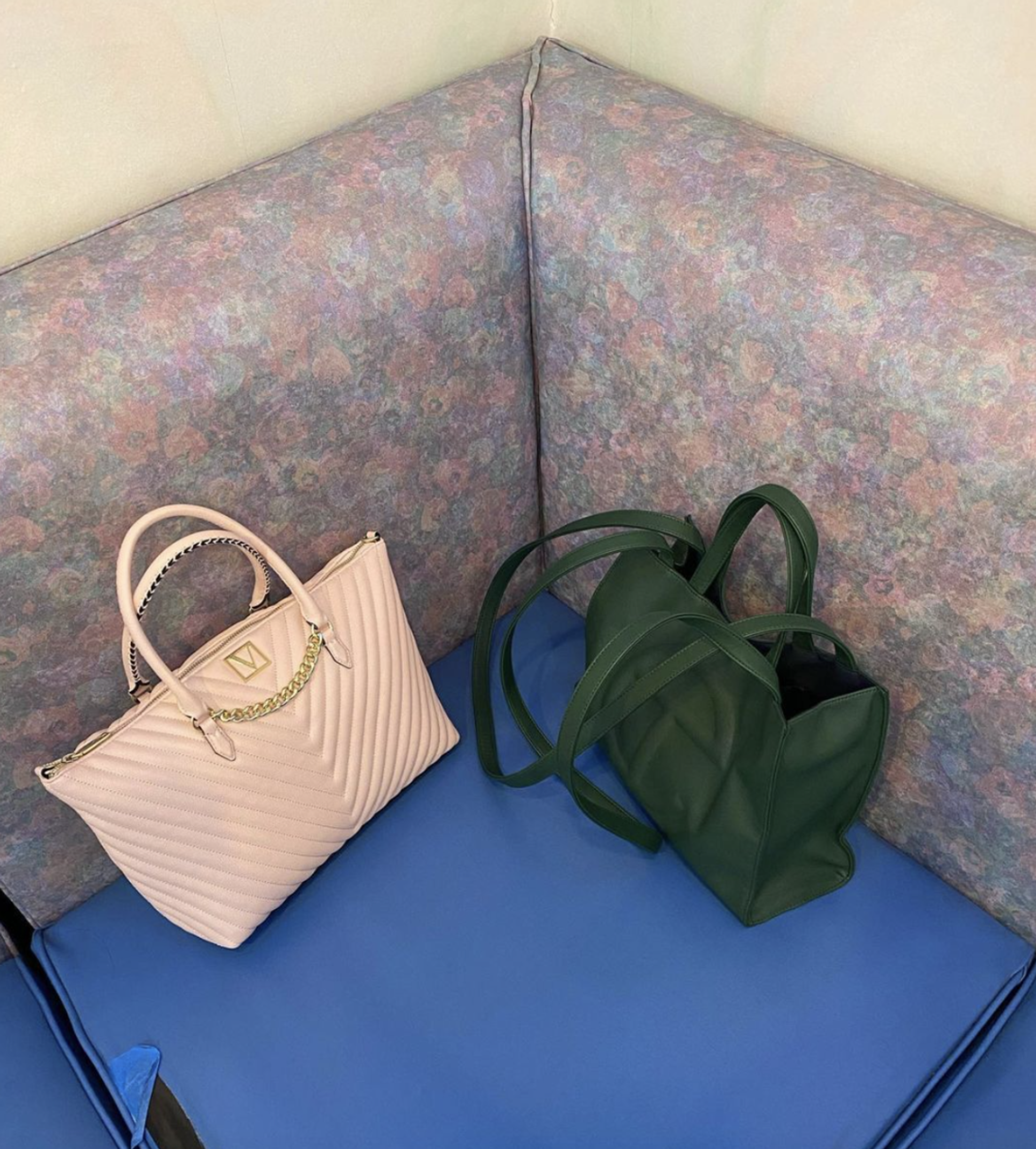

My mom’s bag and my Telfar bag. Taken by the author for Instagram, 2020.

I posted this image to my Instagram on September 8, 2020; it shows my mom’s pink Victoria’s Secret bag next to my green Telfar bag. We were sitting in the waiting room of Blue Sky Dental in Chinatown for our annual teeth cleaning. She loves Victoria’s Secret. She waits for coupons, stalks the stores. And I was recently enamored by Telfar, a trendy unisex brand founded by the queer, Black designer Telfar Clemens and popular with Bushwick artsy types. My mom raised an eyebrow when I told her that I had spent over $100 on the bag, which is made out of vegan leather (i.e. plastic). “For Everyone,” the second essay in my book, grapples with the differences in our taste. To me, I wanted the essay to enact a gesture similar to Stewart Uoo’s Untitled, or Ken Okiishi’s Wish I Were Here: a record of reaching across artistic generations.

My parents’ garage.

“For Everyone” inspired me to look further into my own life. I wrote about the clutter and hoarding in my parents’ house that I tried to help clean up when I was living with them during the pandemic. My parents didn’t want to throw anything away, but I did. Why couldn’t they let go of all this stuff? What did I want by throwing it out? I learned that Ken had actually made an installation out of all the stuff in his own parents’ basement in 2018, and it made me think of this junk differently, as “fat to cushion the impact of immigration.” That’s the phrase I use in the first essay in the book, “A Model Childhood,” which is named after Ken’s work.

Ken Okiishi. A Model Childhood, the mainland (Ames, Iowa), circa 1978-2001, 2018. HD video, DV family history video for insurance purposes, data point cloud generated by 3D scan and one car load of personal effects transported from Okiishi family basement, 2940 Monroe Drive, Ames, Iowa. Dimensions variable

I imagined turning my parents’ possessions into an installation. And then, somehow, I did. In the spring of 2022, I asked my friend, the gallerist Helena Anrather, for a summer show, and “Victoriassecret” was born. In this exhibition, I brought together a bunch of things from my parents’ house—as well as works from Stewart, Ken, and other artists I admire—a physical embodiment of the literary approach of “A Model Childhood."

Simon Wu. Installation view of Victoriassecret at Helena Anrather, NY, June 10 - July 29, 2022.

When I put words to it—this impulse to look across generational gulfs to understand art and history—I started seeing it everywhere. I probably can’t overstate the influence that Maggie Lee’s 2015 film and installation Mommy had, and continues to have, on me. The piece documents Maggie’s mother’s life, the artist grieving her mother’s death, then eventually having to clean out everything in their New Jersey home. The best way I can describe seeing her film and installation at the Whitney is to note the pang! of recognition it struck in my chest.

Installation view of Maggie Lee’s Mommy (2015) at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

I started looking further back into history, toward artists and collectives from a past that seemed to bubble just below the surface of where I was. I fell in love with an image of Bob Lee and Eleanor Yung, the founders of the Asian American Arts Centre in Chinatown, dancing at a post-opening after-party in 1982, because it made the past feel more joyfully present. Through my research, I became friends with Bob and Eleanor, and learning about the path they forged, as Asian American cultural workers, made my own work in museums feel like it had a lineage (“Without Roots But Flowers,” the fifth essay in the book). They danced, so I felt I could.

Gene Moy. Bob and Eleanor Dancing, 1982.

I probably put more of myself into my reading of these historical images than is permissible for a proper art historian, but that was okay, because the book was also the process by which I realized that I didn’t want to be an art historian—or not only that. I wanted to have idiosyncratic, irrational, and emotional reactions to art. I wanted affairs and trysts with art, not only journal articles and monographs. I often imagined what it would be like to live as these artists did. This candid photograph of the artist Tseng Kwong Chi became increasingly important to me.

Tseng Kwong Chi at Mr. Chow’s.

Tseng Kwong Chi is known for his rigid, conceptual photographs for which he dressed up in a Mao suit to visualize the “Chinese national” he was implicitly perceived as by white Americans. But the truth was that he was decidedly of the diaspora, growing up in Hong Kong and Paris before studying art in New York. The Mao suit was a projection of what everyone saw of him––a China man––and I was upset thinking that art history had condemned him to a caricature of himself. Even if Kwong Chi had perhaps devised his legacy to be that way, I despaired. I imagined that his fate was my future. So I dug around in the archives for his image, without the Mao suit, where the artist is pictured as just Kwong Chi, and it became my sandbar in the waters of history, a place to rest knowing that his image would persist beyond stereotype.

From relevant, to revelation, to relative, my writing was guided by intuition and devotion. Before I began the book, I knew two things for sure: that it was going to be called Dancing On My Own, after the combination of ecstasy and melancholy Robyn captures so beautifully in her 2010 song, and that a painting by the artist Leon Xu, an artist I first learned of through Helena Anrather, who ran the gallery where Victoriassecret appeared, might appear on the cover. Every Little Kiss (2018) captures it all. It’s a shimmery, there-but-hard-to-describe feeling of elation, sadness, and possibility. In the last chapter in the book, “After, Life,” I talk about learning from my boyfriend Ekin that the Turkish word for the way moonlight sparkles on the surface of water is yakamoz. I swear I did not know that word before I picked the cover, it just happened to work out that way, but it’s all there in that painting. It’s nostalgic but also hopeful, it’s happy and sad: yakamoz. It's presumably of water but the longer you look at it the more it starts to dissolve; the sparkles start to look like galaxies. Like a city zoomed out very large, like a roll of film in the archive, a glossary of drawings in DeviantArt, or the cosmos, all in the palm of your hand. ♦

Leon Xu. Every Little Kiss, 2022.

Subscribe to Broadcast