"It Bears an Imprint, However Small, of You"

Editor's Note: Asuka Goto was born in Massachusetts to a Japanese father and an American mother. When she was fourteen years old, her family moved to Yokosuka, Japan. She knew her father as a stoic man; yet, she observed, he became differently-animated when he spoke in Japanese. An aspiring writer, he would squeeze in lines between his day job, eventually publishing several Japanese-language novels.

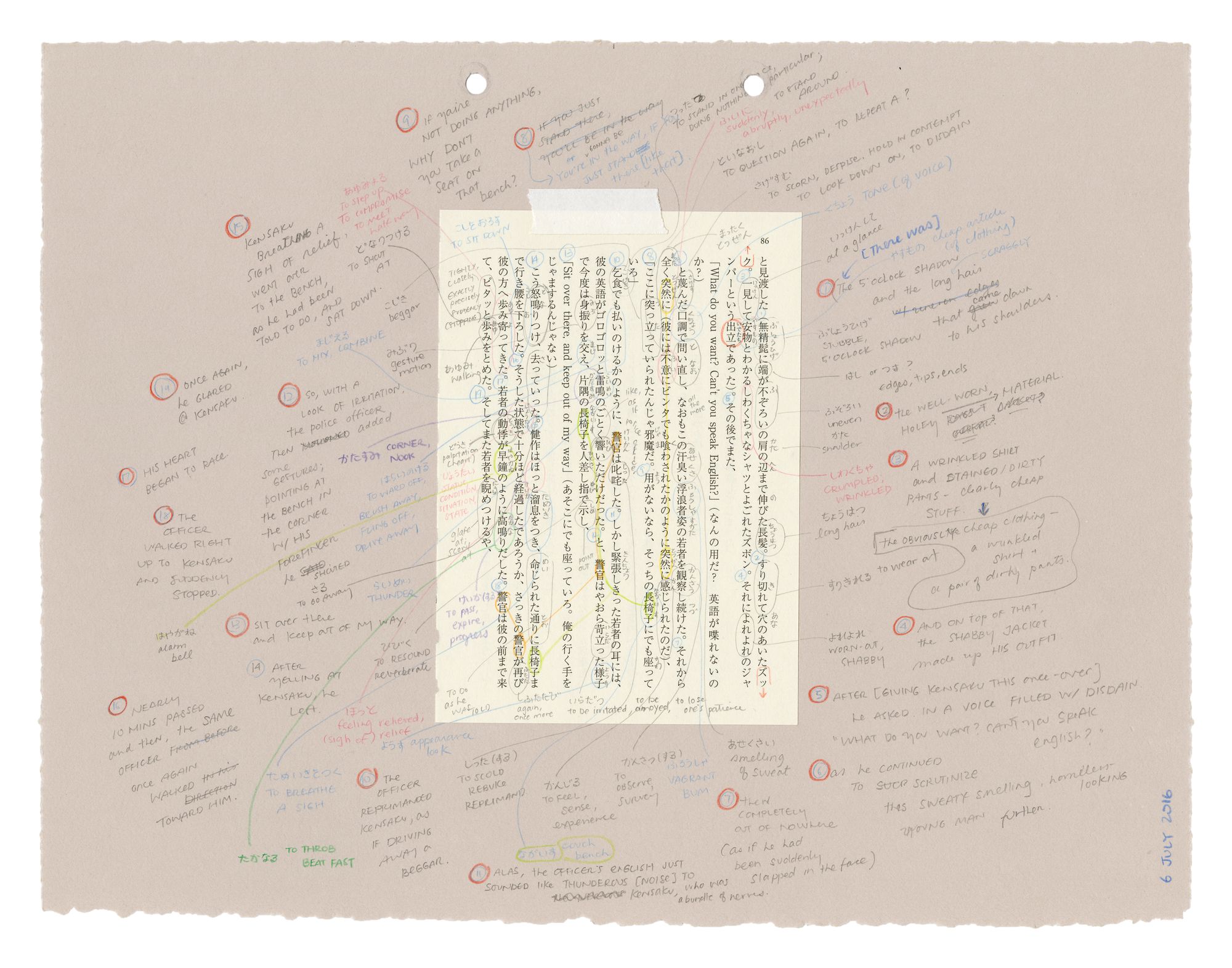

Drawn to find an entry into his mysterious artist side, Goto embarked on the steep task of learning Japanese to read and translate his novel Elizabeth. She presented this three-year endeavor in an exhibition called “lost in translation” at Tiger Strikes Asteroid in Brooklyn in 2018. During her 2021/2022 Visual Art Residency at Pioneer Works, she worked on adapting the project into an artist book, called To Send a Telegram.

On a hunch of shared affinities, Broadcast reached out to film programmer, producer, and Japanese-English translator and interpreter Aiko Masubuchi to join Goto in conversation. Masubuchi has translated writings by Haruki Murakami and Aki Onda, and interpreted for filmmakers such as Kazuo Hara, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, and Shinya Tsukamoto. Her translation of a short story by counterculture icon Izumi Suzuki was published by Verso Books in 2021 as part of the collection Terminal Boredom. As we surmised, the two had much to get into.

Since this is our first time meeting, can you tell me a bit about yourself?

I'm calling in from Tokyo right now. I was born and raised here, in the east side, called Shitamachi. The area has historically been more working class and full of small shops and alleyways. My dad's an acupuncturist, born and raised in this neighborhood. He’s been an acupuncturist for almost five decades now.

I grew up around all sorts of people who came to see my dad. I did my homework in the waiting room where my mom would serve tea. My dad places a lot of emphasis on hearing people’s stories and woes. He says half his practice is acupuncture, the other is to listen and chat.

Perhaps because of that upbringing, I realized that I wanted to grapple with people's stories, in a different way. In Japan, I went to a high school called Yokohama International School. At NYU, I studied a combination of literature, anthropology and film. We got to title our own concentrations and I named mine, “The Production and Consequences of Narratives.” I’ve been out of school for a while now but these questions still interest me and I think are relevant to your project––why people tell stories and what results from these acts.

I'm familiar with the International Schools because when I was in high school in Yokosuka, our sports teams would compete with them, including YIS.

Yes, that’s the one! What about you Asuka? I’ve had the chance to look at your work, but would love to hear more about you.

I was born and raised in Boston, to an American mother and a Japanese father. When I was in ninth grade, my mom was offered a teaching job on a U.S. military base in Japan. My family moved to Yokosuka and I ended up finishing high school on the base. Although I lived in Japan for three years, I lived within an English-speaking community, went to an American high school and had all American friends.

I just have to say that I was really moved by your work, the dedication that was communicated through the process. How did you start?

Thank you. I started this translation because I wanted to understand my dad as a creative person. I knew a bit of Japanese starting out––my dad would speak to me and my sister when we were little and I also studied the language in school––but I've never been able to speak comfortably or read a real book in Japanese.

In the beginning, I was looking up all the kanji by strokes, or radicals when I could determine them. But often I couldn't so I was counting strokes, sometimes miscounting, then hunting for these characters in the dictionary’s index. Eventually it occurred to me that there had to be a modern way of doing this, which is when I realized I could use the trackpad on the computer to draw and search for the characters. From there, it moved much more quickly.

The kanji element of Japanese always makes it trickier because when you come across an unfamiliar character, you may be able to see it and maybe even decipher the meaning but have no idea how to say it. It’s a strange feeling.

In English, if you don't know what the word apple means, you turn to the A section of the dictionary and go from there. But in Japanese, when you have no sense of how the word is pronounced, you can’t even look it up. That's part of what made this project so difficult, that people familiar with logographic or symbolic writing systems will appreciate. When I say that I looked up every word in the dictionary, first, I needed to find out how to pronounce the word, phonetically.

Since you began this project in part to get to know your dad better, were there any surprises for you?

It revealed his awareness of details that I thought he paid no attention to. There was this particular passage where he describes a little girl, and the necklace and headband she was wearing. And I didn't know that he knew about women’s accessories, you know? [laughs]

I have a question for you, Aiko. In your interview with the film director Ryusuke Hamaguchi, you spoke about how the process of interpretation doesn’t involve a “one-to-one-conversion” but is rather an internal unpacking and repackaging. And because this process happens within you, it seems inevitable that the interpretation must bear an imprint, however small, of you, the interpreter. When we talk about interpretation in other creative fields––in music, in theater, in dance––we acknowledge and even embrace the mark of the performer. But in language translation and interpretation, it feels as if the goal is, somehow, faithful neutrality. Can you talk about that paradox?

It's worth noting here that I never studied to be a translator, and so though I do get paid to translate, I can't speak to any industry standards. Translating has just always been a part of my life. Neither of my parents speak English and yet they sent me to a school where all the teachers spoke English. As a ten-year-old, I was interpreting my own parent-teacher meetings.

What I do now feels like an extension of that––including the awareness that my own emotions are involved in the act of interpreting.

As a child, were you aware of your position of power?

I wish I was smart enough to recognize that! I could have made myself sound like a perfect student, which I wasn’t. But as a child, I earnestly wanted to bridge the gap between my life at home, from a working-class, non-English speaking family, and my life at school that was surrounded by English-speaking and expat families. I wanted my parents to understand as much as possible.

This question of power is interesting to me and I was wondering in what ways you felt power when you were translating your father's words. I think this power has the potential to be dangerous, too. You hold the ability to manipulate meaning without the original author knowing.

You also said that the work was originally for yourself. Did your approach change when you started thinking about presenting it to a larger audience?

I was particularly sensitive about my father’s novel in a way that I'm not sensitive to the writing of other people. For instance, there's quite a bit about the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and the American Indian Movement in the book. I was aware that my dad was writing to a Japanese audience, who would require a certain amount of context about both politics and race relations in the U.S. in the 1970s. Still, I found myself questioning the way in which some of that content was delivered. Because of this, I feel very protective of the original text.

In the essay you write in To Send a Telegram, you tell the story of how you presented this work at the Brooklyn Public Library. Your dad came to the reception and was confused. He said, “we didn’t see your work. That’s my work on display.” This issue of artistic ownership intrigues me, and I’m curious about how that conversation went afterwards. Did his puzzlement remain?

I started this project because both my father and I had creative practices that were inscrutable to each other. Ultimately, this piece, which was intended to bridge that gap, has become just another one of my works that he didn’t understand! Despite his confusion, he supported me in the ways he knew how. When I had questions, he tried to answer them. So perhaps this piece was, in a way, a collaboration between us.

Your project, which lives in the personal, emphasizes something really important about the gesture of translation that can sometimes be forgotten when it's professionalized. These days, I've learned to be picky about translation projects because it’s a lot of time spent with somebody's thoughts.

That makes sense. All of your translation work feels deeply linked to you as a creative person. What are your thoughts on translating for, say, grammatical or semantic fidelity versus spirit? It seems like you favor the latter.

I care about the order that images appear. To me, that's the pleasure of reading. But because of the difference in grammatical structure between the two languages, it's not always possible to recreate the same order of the original. And so I'm often of the mind that "this can be grammatically wrong in English, but the experience of reading this is much closer to the experience of the original." Though, of course, there’s always a degree to how much that can be pushed.

I've recently learned about this wonderful zine called Chogwa, edited by a translator called Soje. For each edition, a group of Korean to English translators translate the same poem and the resulting translations are wildly different from one another. I love how different they are.

When I used to talk about my project, I often described my translation as flawed or imperfect. Once I had a studio visit with a translator of Polish poetry, and was using that kind of apologetic language. She interrupted me right away and said, "I want to disabuse you of the notion of a perfect translation." Her assertion made me think about it in a new way, that it isn’t a process that leads to a specific destination but is an exercise in exploring a wide range of possibilities. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast