The Rhythms Remain

There’s a reason that Joe Boyd’s new book—a doorstop of a tome as weighty and colorful as the huge subject it charts—lands bedecked with blurbs from the likes of Brian Eno (who says “I doubt I’ll ever read a better account of the history and sociology of popular music than this one”) and David Byrne (“A big one… but a page turner”). Boyd’s name may not be as well known as those famous paragons of music and taste (at least in the United States: in Britain, where the American-born producer has lived for decades, he’s a regular commentator on the BBC). But among cognoscenti of the rare nexus where popular sounds and worldly erudition meet, Boyd is a venerated figure. His storied career in music began as the stage manager who plugged in Bob Dylan’s guitar at Newport. He managed Muddy Waters’ first European tour. And then he stayed on in England, as a budding producer in thrall to rock’s folk roots, to launch the careers of Nick Drake, Pink Floyd, and Fairport Convention.

Other production credits, from those early years, included seminal records by the reggae legend Toots Hibbert and two sisters from Quebec—Kate and Anna McGarrigle—whose superb songs shaped the repertoire of Linda Ronstadt (and of Kate McGarrigle’s kids, Martha and Rufus Wainwright). Boyd’s 2006 memoir, White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s, is our best account of the transatlantic cultural complex that shaped the sonic gestalt of the Woodstock generation. But in the decades after those covered in that book, his ears led him further afield. In 1980, Boyd launched Hannibal Records to release records with musicians he loved from locales ranging from Cuba to Bulgaria to New Orleans, and which he marketed to consumers under a tag—“world music”—that he and fellow purveyors of such sounds coined to get their wares into stores like Tower Records and Sam Goodie’s. In recent years, he and his wife Andrea Goertler have split time between their London flat and one in Tirana, Albania, where they’ve been making records with the unheralded greats of Balkan polyphony.

When I first met Boyd, 15 years ago in California, he was helping produce a film whose shooting he’d overseen decades before, in a church in South LA, that’s since won due acclaim for capturing Aretha Franklin at her very finest. He was also just beginning to write what would become And the Roots of Rhythm Remain. When he shared with me a hundred-page draft of a chapter about the epic history of South African music that helped make Paul Simon’s Graceland a global hit, I knew this was going to be a hell of a book. I didn’t know it would be composed of this and seven other such chapters—on the musical cultures and global influence of Cuba, Jamaica, India, Brazil, Argentina, and Eastern Europe and Western Africa, respectively—that each alone would comprise authoritative books on their subjects. Taken together, they add up to a magnum opus that’s equal to its blurbers’ praise and which saw The Guardian dub its author "the Proust of music.”

It was a treat to sit down with Boyd at Pioneer Works in September, at his first event stateside for this remarkable testament to his life’s work. The following is drawn from our chat for Broadcast Radio Hour, and another conversation that followed.

The title of this new book of yours, a magic mountain on the history and mixing of musical cultures from around the world, and your engagement with those cultures as a producer of brilliant records, is borrowed from Paul Simon. It comes from his lyric on Graceland, that once-controversial album, born of his collaboration with the great musicians of South Africa, that’s endured as a masterpiece. His phrase about the roots of rhythm alludes to your own core beliefs, about the import and evolution of rhythm, as evolved and mastered and shared by humans, not machines, which we’ll talk about. But I want to first ask you about the book’s subtitle. You call it “a journey through global music,” not a journey through “world music.” Why?

Well, that’s intentional, yes—and in part a dodge because “world music” has become a vexed term. It's a vexed term, as it happens, that I had a part in creating. With the heads of other independent labels, we realized, back in the middle ’80s, that we needed to find a way to get these records we were making—records that didn’t fit typical genres, with lyrics often not sung in English—into stores. It was an attempt, really, to capitalize on a phenomenon that was already there—I tend to think it had something to do with a low pressure zone, in Anglo-American popular music, in the era of punk and disco. There was not as much music that satisfied a certain taste, or need, among people who started looking further afield for virtuosity, spontaneity, roots. So there was an audience there. And an inescapable fact about that audience was that someone who already owned a Nusrat Fateh Ali Kahn record was actually quite likely to be interested in an Orchestra Baobab record, or a Swedish fiddle music record, or the Luaka Bop Brazilian compilation.

The critique of how this played out, of course, is that it had the effect of “othering” anything that wasn’t Western—critiques I know you share. But it also had the effect of setting up an infrastructure for many artists who hadn’t previously been able to tour internationally, to make money and get checks from ASCAP and BMI, to evolve their art in a global context. To take part in an exchange of musical ideas, in new ways, that have been at the heart of musical evolution everywhere. As you write in the book, “We weren’t so much defining music as defining an audience.” And you’re clear that this act of doing so—in the real world of marketing—of keeping your labels afloat and paying artists—should really be seen as a moment in this far larger history, often centered outside the West, that you recount here.

Right. My question to people criticizing the term has always been: Are you criticizing the idea of a Western audience for music that was sung in non-English languages, or do you think that’s a great thing, but you just don’t like the term “world music”? Whatever term you apply will be subject to the same accusations—that a privileged, white power structure is categorizing music of cultures that have less financial power in the world. But if you don’t use every means you have to sell those records by wonderful artists from places that haven’t had access to the Western market before—that to me is really criminal. As you say, and as I write in the book, that "world music" moment is but a pin-prick—a footnote, a teeny detail—in the larger global history I’m interested in.

Because my main point here is that people, everywhere in the world and throughout history, have been fascinated by different kinds of music. That has always been a dynamic force in any culture—despite what nationalists might say about how “this music is pure; this music is ours.” Because it never is. Whether music in Africa or America or Europe—where so many traditions were influenced by the Roma, by enslaved Africans, by trade and sailors in waterfront bars. That’s how music evolves everywhere. My book is about that process—which accelerated like crazy after the mid 1920s, when recording technology changes and records could travel, and sounded really exciting. And you suddenly had people listening to Jimmy Rodgers all over West Africa, you had Cuban records in the Congo. And you start having this cross-cultural effect.

That "world music" moment is but a pin-prick—a footnote, a teeny detail—in the larger global history I’m interested in.

And the same applies, of course, to the United States, what we think of as “ours”—jazz, rock and roll—is also deeply Cuban. The riff in “Louie Louie” is Cuban. The “Spanish tinge” of ragtime was the habanera, which hit New Orleans from Havana across the gulf. Or Jamaican music, from the 1950s on—this is another great allegory—producers on that little island loved American soul but riffed on those sounds to create their own sounds—ska, reggae, dub—which became hugely influential in the north. One thing the book highlights again and again, is that this isn’t, and never has been, a unidirectional story. It’s not just about how non-Western music became popular in the West—or vice versa. It’s about cross-pollination, how things move back and forth.

Right. I loved discovering that when Tinawaren—the Malian heroes of “desert blues”—were living in the desert, fighting as guerillas for Tuareg independence, when they were sitting around the campfire with a ghetto blaster—their favorite tape to play was Dire Straits.

You can’t tell people what to get into, or respond to. Music moves, these circuits don’t respect borders. Which is a nice segue, as we ready for our annual 24 Hour Ragas Festival at Pioneer Works, to one of the great emblematic stories of a particular East-West dialogue in music, in the latter decades of the twentieth century. I’m alluding to Indian music—and North Indian classical music’s conquest of the West, via the Beatles and otherwise, and the evolution of those traditions with Ravi Shankar.

Oh yes, there’s a lot of that here. Starting with Dick Bock, and Zsa Zsa Gabor’s bathtub.

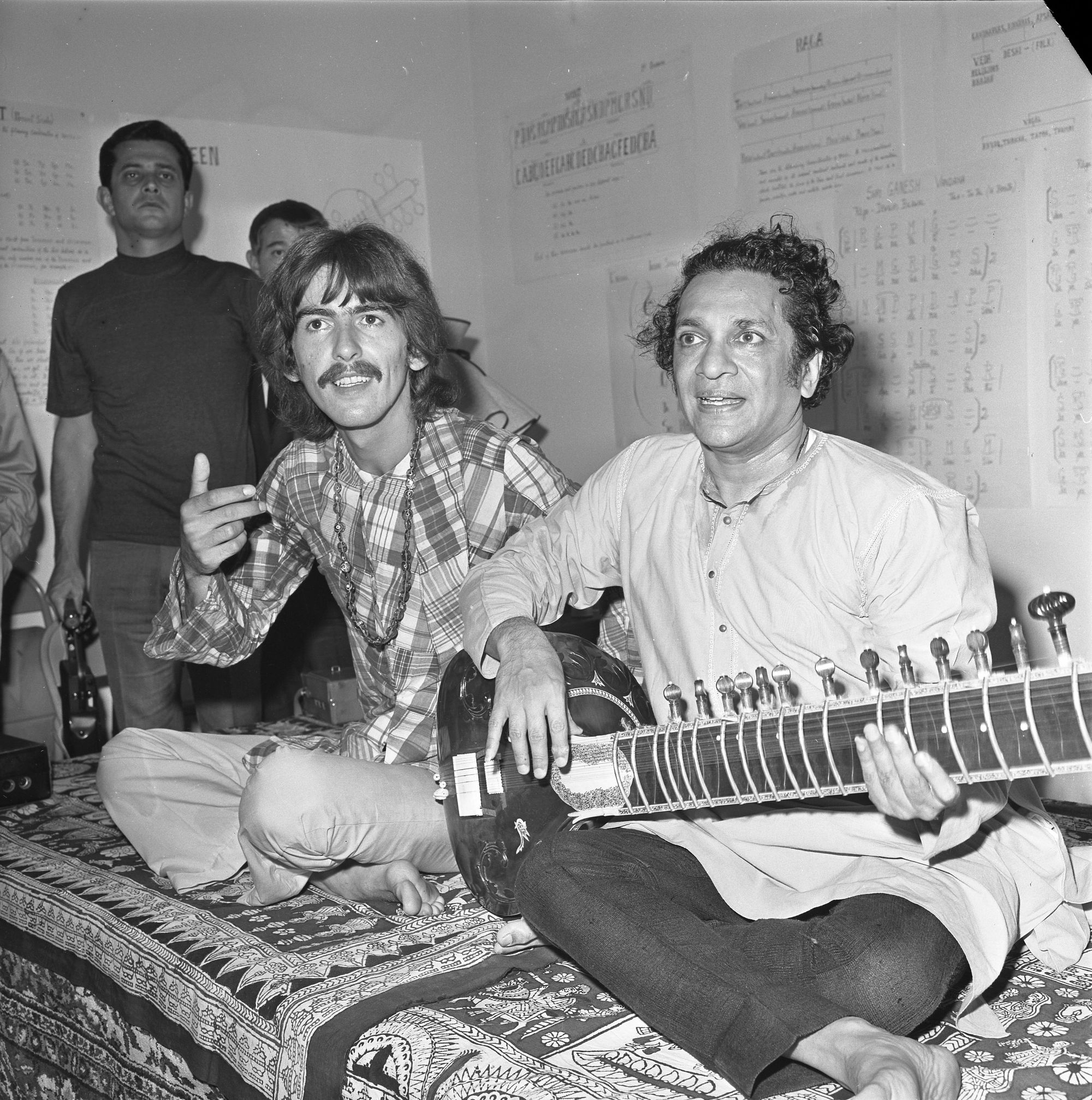

Right, that amazing story you recount—about Dick Bock, this rather obscure jazz label head in California, who happened to see Ravi perform in New York, and made a record with him that he handed to David Crosby in L.A., who in turn showed up at Zsa Zsa Gabor’s mansion in Beverly Hills, which the Beatles were renting, in 1965, after they played Shea Stadium and for some mid-tour R&R. Which is where, in Zsa Zsa’s bathtub, Crosby turned George Harrison and John Lennon onto the wonders of Indian music.

Right, and the next thing you know you had “Norwegian Wood” and “Eight Miles High.” And also this really sweet, tender friendship between Ravi and George Harrison—which they both owed, really, to George’s wife, Pattie Boyd, who hit it off with Patricia Angadi, a fellow Home Counties girl, vaguely posh, who’d married Ayana Angadi and ran this London organization, the Asian Music Circle, that was a kind of meeting place for Indian musicians. Before they met, Ravi really wasn’t interested in the Beatles. But these two women became friendly, and so did their husbands. And one night at dinner, the Angadis introduced Ravi to Pattie and George.

Who in turn hit it off. And George’s devotion to Ravi, as you write, was profound. Not only to the music, and the time he spent in India and collecting his recordings to release with EMI. But also this friendship begat, for example, the Concert for Bangladesh—the first big celebrity benefit concert. I was so fascinated, in the larger story of Ravi as you write it, by the extent to which he comes from a family—his father was based in London, his big brother had a dance troupe—who were engaged, long before he turned up, in bringing Indian culture in the West. He grew up in India, and was steeped in this deep tradition of Rajasthani music—this courtly tradition of improvisation, dating from the Mughal empire in the sixteenth century. But the ragas that Ravi brought to the west were also consciously shaped, by him and his mentor Allaudin Kahn, to translate cross-culturally.

Yes. That’s what his father and his brother had always done—what they’d gone west to do. His father was a lawyer, but really he was most interested in these pageants he put on, not particularly successfully, that would sell Indian music to a western audience. And so Ravi came from that background. But what he did with his mentor, Allaudin Kahn, was also to take what had been the discrete parts of these six or eight hour shows––the slower alap and jor, followed by the mid-tempo gats, the rapid jhala—and collapse them into one two-hour concert. Which is how you got that sense of dynamic range, what David Crosby described as “the slow and reflective beginning, the gradual build,” that he dubbed “very emotional and sexual.”

Hippies went nuts for this, as we know. But it’s also interesting how it played back in India. At first, the way he was presenting the music was ridiculed—people weren’t sure. But then that changed.

Yes. When Ravi first toured in the West, he was mocked in the Indian press. For his short concerts, for Alla Rakha’s solos on tablas. But within ten years, concerts that were two hours long and had all those elements were drawing big crowds in Delhi and Mumbai and Madras.

These six and eight-hour concerts had been the rule before, which had to do with this aristocratic view of Indian classical music—that it was for the elite; it was for the educated. And Ravi was so committed to trying to open it out, to get it on the radio, doing these concerts. You know, people had to get up in the morning to work. They didn’t have a bunch of servants bringing them tea at 11 o’clock after they’d been up until 3:00 for an evening raga. So there was a big democratization process, in Ravi’s altering of the structures of presentation.

That’s what was going on in India. But you also write about how, quite beyond how the sitar came to adorn pop hits like “Norwegian Wood” and “Eight Miles High,” there were deeper musical currents happening, for other musicians at that time, in other realms.

Yes, absolutely. With regards, in particular, to these two huge fundamentals of music—rhythm and scales. Alla Rakha was a huge influence on Mickey Hart, from the Grateful Dead. They would meet up and have these sessions, playing these complex games. Rakha would lay out a ten-beat cycle on the tabla, and yell out a number—seven, nine, whatever—and Hart had to overlay that number of beats evenly over Rakha’s ten.

Each of them playing a different pattern, but aiming to land back to the one at the same time.

Right. And Mickey Hart said that, really, that’s the basis of the jam band—rhythmic complexity married to a modal sense of harmony. Where you basically just lock into one root note, and improvise off that note. It’s not about changing chords. It’s like a raga—this is what jam bands do.

For better or worse.

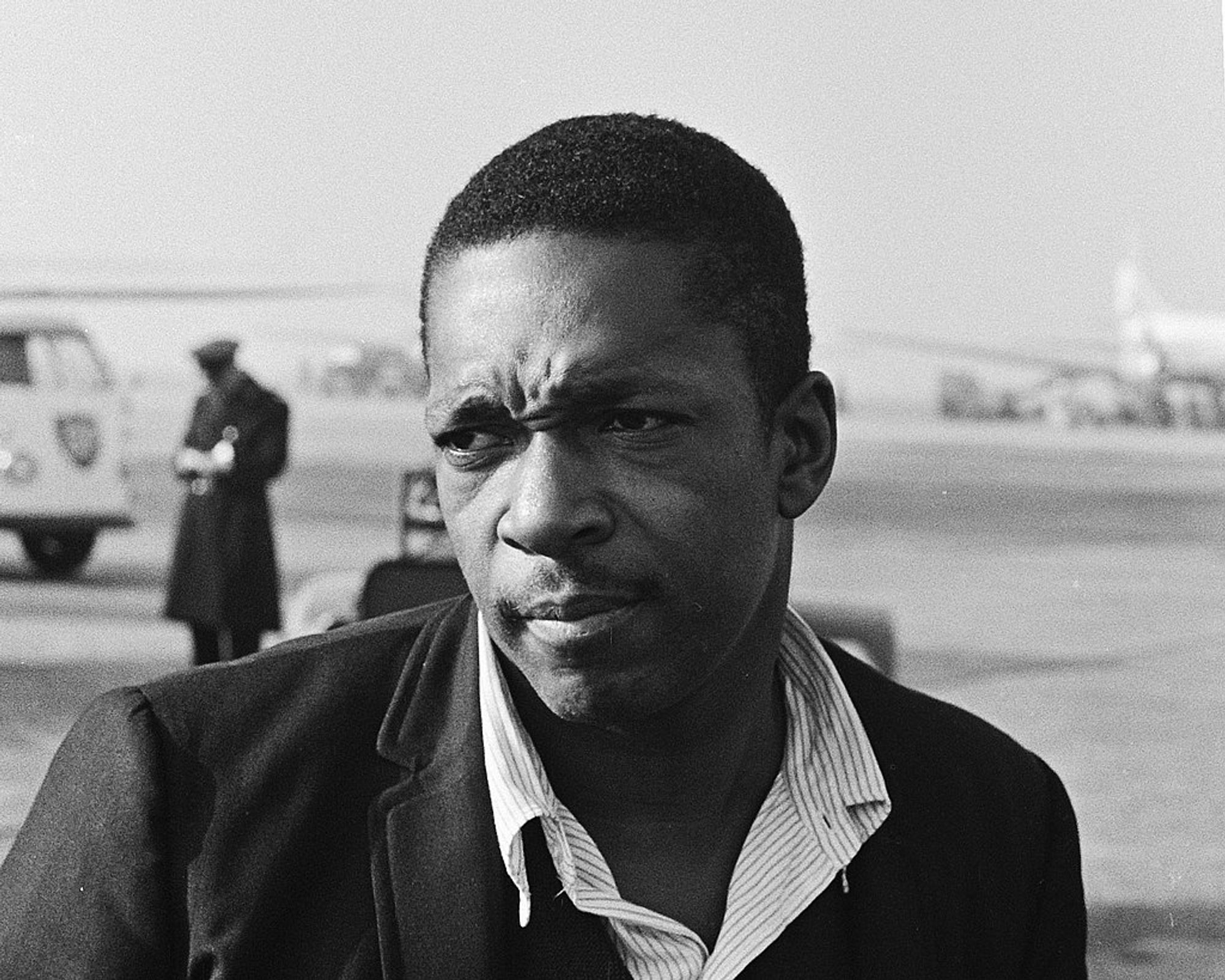

And both elements, too, were fundamental to John Coltrane, and his revolution in jazz. One of those things I loved discovering was that what really started that journey for him was playing for six months at the Five Spot in New York, with [Thelonious] Monk, in 1957. He was constantly hearing Monk play these dissonant notes, two adjacent notes—like he was aiming for B and hit both B and B-flat. He’d play them at the same time, and it could sound like a mistake. But it wasn’t a mistake—it was because he heard a tone between the tones. And he was trying for it.

That led Coltrane to explore Indian music. In Indian music, there are no frets or keys or valves. It’s a continuum, from one note to its octave. There are any variety of mathematical formulae to structure a key; here it’s not eight notes, it’s five or six. It’s often different on the way down. And the notes it hits, on the way up or down, often aren’t the notes on our frets or keyboards.

Coltrane was so liberated and excited by this discovery—that the Western way of looking at music was just Western. He and Ravi Shankar became friends, too.

Coltrane named his son Ravi. And his wife Alice Coltrane, of course, made remarkable records in this direction.

With regards to the influence and central place of India, writ large, in global music, there’s another deeper history, in a way less known, that you dive into here. That’s the story of the Roma people, once pejoratively known as gypsies, who arrived in Europe from the subcontinent centuries ago, and who have since played a huge role—from their camps and caravans outside towns—in shaping its culture. Most famously, perhaps, in flamenco in Spain and in the person, in France, of the great jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt.

Yes. There were two waves of Romani immigration into central and Western Europe. One went back to the 15th and 16th centuries, when they first arrived in Europe with the Turkish invasion. The Turks were stopped at the gates of Vienna, but the Romani kept going, some of them. They spent three and a half centuries as slaves in Romania. Slavery was eventually abolished in the mid-nineteenth century. And there was another wave [of migration] into France, and that included Django Reinhardt's parents. He started playing on the streets of Paris at age eight with a banjo, with a guitar neck. And by the time he was 12, he was playing with bands in the bals musettes, which was this tradition that came from the Auvergne that was very popular in Paris. He ran circles around everybody. And then one night he was passing a nightclub and he heard African American jazzmen.

It blew his mind, and it started this quest in his life, and it was interrupted by this terrible fire in which his hands were burned, and he lost the use of the fourth and fifth fingers on his left hand. So he had to fret. Every solo he every played, he played by wrapping his thumb around the neck to fret the bottom string, with two fingers on the other strings—and the music he made, through the German occupation and after, what he did with his love for jazz, for Afro-America, with his particular Romani sense for melody and speed, was just so important.

Django Reinhardt at the Aquarium jazz club in New York, NY

Photo: William P. Gottlieb, Courtesy of the Library of CongressAnd the way into that story for you, here, is recounting your first encounters, in Paris in 1964, with so-called Manouche jazz.

Yes, I was managing this tour with Muddy Waters and all these amazing Black American artists—Sister Rosetta Tharp, Reverend Gary Davis, Cousin Joe, Brandy McGinn, Sonny Terry, Otis Span. We’d just done two and half weeks in Britain. In the spring of ’64, no white clubs or festivals were booking these artists. And suddenly they were in Britain, and there were queues of teenagers waiting for an autograph. It was fantastic. And the atmosphere between the musicians was amazing, too. They were all from different parts of the country and different sub-genres, et cetera. But by the time we got to Paris, where we'd had one big concert at the television station, there was this fantastic bond.

And we arrived in Paris and we got taken to the hotel and the producer said, "Does anybody want to hear some music with your lunch?" And Muddy and Sister Rosetta and I and a few others said, "Sure." And we jumped in a van, and they took us to the flea market on the outside of northwest corner of Paris. And we went into this cafe and there was that sound of “the pump,” that four-four strum and a violin solo. Everybody was entranced. And I discovered it was Joseph Reinhardt, Django's brother. Django had died 10 years before. It struck me, at twenty-two, as the most French thing I’d ever seen. But there was nothing French about it.

And as you write, what Django did with the guitar traveled back across the Atlantic and shaped Black music here, American music, in some profound ways.

Yes, there’s a passage in the book that shows how. As I put it there:

In Django Reinhardt's charred hands, the oppressed cultures of African-Americans and Roma were joined. He was proud of his heritage, but aspired to Blackness, worshiping first Armstrong, and Ellington, then Parker and Gillespie as gods. He would've been gratified had he known that West to East wasn't the only direction. Influence flowed across the North Atlantic. A young American guitarist stumbled on some hot club 78s in 1947 as he was starting to explore the instrument's possibilities. "Django's ideas lit up my brain. He was light and free and fast as the fastest trumpet running through chord changes with a skill of a sprinter and the imagination of a poet. I loved Django because of the joy in his music, the light-hearted feeling and freedom to do whatever he felt." Which nicely sums up how B.B. King, the author of that quote, transformed blues guitar.

Superb. The B.B. King reveal.

Yes. Because when you think about BB King, it's very bluesy, but he adds that touch of melody—which I never would've thought he might've come from. But you hear that and say: "Whoa. Okay." It all connects.

One of the things I love about this book is that you are writing, in a sense, as a historian—as someone who is deeply knowledgeable about so many different areas of music and cultural history, who’s consulted libraries full of sources. But you're also writing as a practitioner. As someone who spent your career in the record business thinking about how to get people to buy records and listen to them and go out to concerts. And in that vein, there are so many stories here where you write with keen admiration about producers, and labels, and record people, who’ve created publics or defined audiences and genres. In the Cuba chapter, for example, you write about how these Puerto Rican musicians in the Bronx, and the heads of the Fania label in the 1970s, turned those Cuban rhythms into salsa—this “Latin” sound that went everywhere.

It's also the case, given the era you’re describing and helped shape, that a lot of the stories you recount can be mapped onto a kind of “white savior” narrative—whether that’s Chris Blackwell at Island Records, figuring out how to sell Bob Marley's reggae to the world, or Paul Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo, or Brian Jones wandering into the Jojuka in Morocco. How do you think about that fact, or the questions it raises?

There are many of those stories, of course. But I think about my role, say, or Chris Blackwell's role, in relation to other producers––I love stories of people who’ve played this role, a vast number of whom, of course, aren’t European. I think of Coxsone Dodd, the great Jamaican producer in the ‘60s; or West Nkosi in South Africa, this penny whistle player from Pretoria who came to Johannesburg and produced Ladysmith, all these groups; Andre Madani, who was Lebanese, and grew up in Paris, was sent out to Brazil to be an A&R man and was responsible for João Gilberto and launching bossa nova. Ibrahima Sylla, from Senegal, whose biggest impact was outside of Senegal, choosing projects to work on from Mali, Congo, Ivory Coast, and distributing them across Africa. So I think you can talk about the white savior syndrome, but to me, the stories I respond to are stories of producers. And that includes, by the way, musicians like Fela Kuti. The way he performed in the studio, as his own producer. He was in charge, with his great drummer Tony Allen.

The mighty drummer Tony Allen, inventor of Afrobeat. Who you interviewed at length for the book. Those amazing stories about him getting Downbeat magazine in Lagos, absorbing Max Roach’s guide to playing hi-hat, and coming up with his own signature figures. These beats that drummers everywhere now study.

Right. And it was Fela, in those sessions, who would stop a take in the middle and say, "Stop. Go back to the top. Let's start again."

Artists sometimes need an enabler, they need a producer, they need somebody who can find the money, who can get it pressed, who can get it out to the public and make sure they get paid.

As Michael Denning writes in his wonderful book, Noise Uprising, it wasn't just the great performers, singers, musicians, who benefited from this moment, starting in the late twenties with electrical recording, that allowed people to hear vivid, powerful, exciting renditions of music from around the world. It was the cultures themselves, particularly colonized cultures. Denning argues that these cultures that had been captured and exploited by European powers gained the confidence to start to fight, to throw off the colonial yoke through records they were inspired to make by listening to, you know, records by Louis Armstrong or Cuba’s Trio Matamoros. And then hearing the Congolese and then hearing their own singers in this context sounding the same, coming out of the same horn of the same record player and thinking, "Hey, we're world-class too." ♦

This conversation took place on September 8th, 2024, during the Second Sundays Broadcast Radio Hour.

Subscribe to Broadcast