What Lies Beneath

“All water has a perfect memory, and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” So wrote Toni Morrison in an essay that urged us to see the meandering Mississippi’s habit of bucking its manmade banks not as flooding, but as “remembering.” The great novelist’s point was metaphoric: she compared the river’s means of “remembering” to a writer’s way of giving words—in floods of imagination on the page—to what our bodies recall. But her claim’s underlying truth is one Eymund Diegel would affirm. He's New York’s foremost student of the creeks and springs that shaped the city’s landscape, and which still flow and gurgle beneath its asphalt today.

Diegel, 61, is an urban planner and self-styled “forensic geographer” who landed here from South Africa in 1991 and has worked for the city ever since. His day job involves turning data into maps for New York’s Department of Transportation. But it’s how he spends his nights and weekends, as a practitioner of what he calls C.S.I.—“creek scene investigations”—that has fed his reputation among members of city groups like the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club and the Billion Oyster Project. To the small but passionate community of New Yorkers devoted to stewarding its waters, Eymund’s feats as an investigator of its once-and-future creeks are legendary. And it’s in this guise that I’ve asked him to meet me in an area of Brooklyn which, like many in this borough whose name comes from the Dutch term for “broken land,” was once composed of more water than soil.

“History is just a fancy word for hydrology,” Eymund says as he unclips his bike helmet on Pioneer Street in Red Hook. He’s a true believer in sandals and jeans, who has spent his morning biking to Williamsburg from his apartment in Sunset Park, carrying water samples in his backpack to the Citizens Water Quality Testing Program. The Program’s main aim, he explains, is to ensure that New York’s waters don’t contain, for boaters and mollusks alike, too many colony-forming bits of fecal bacteria. (“We want way less than the 24,000 parts per 100 milliliters,” Eymund says, “of what I call ‘poop in the martini glass.’”) Testing outflows from city storm-drains in this way, he explains, reveals strikingly high sums of other trace elements, too. One of these, in this city that doesn't sleep, is caffeine. Another, because of its citizens’ use of antidepressants, is methadone. If you’ve ever wondered why a growing number of mummichog (“mud minnows”) in the Gowanus Canal have been born female, Eymund has an answer: “Estrogen, from birth-control pills, in our pee.”

These are some of the ways that studying the city’s effluvia can help illuminate its present. But Eymund’s gaze is squarely on the past as he looks up Pioneer Street and starts riffing on the routes of Red Hook’s roads, the heights of its buildings, and why certain blocks boast mature London planetrees and others, potholes. And today he’s deputized me, as an enthused agent-for-a-day of his C.S.I. corps, to explore how Red Hook’s old creeks and springs shaped the neighborhood—and still do today. “A creek scene investigator must draw on many sources,” he says, unzipping his backpack to pull out a few of them.

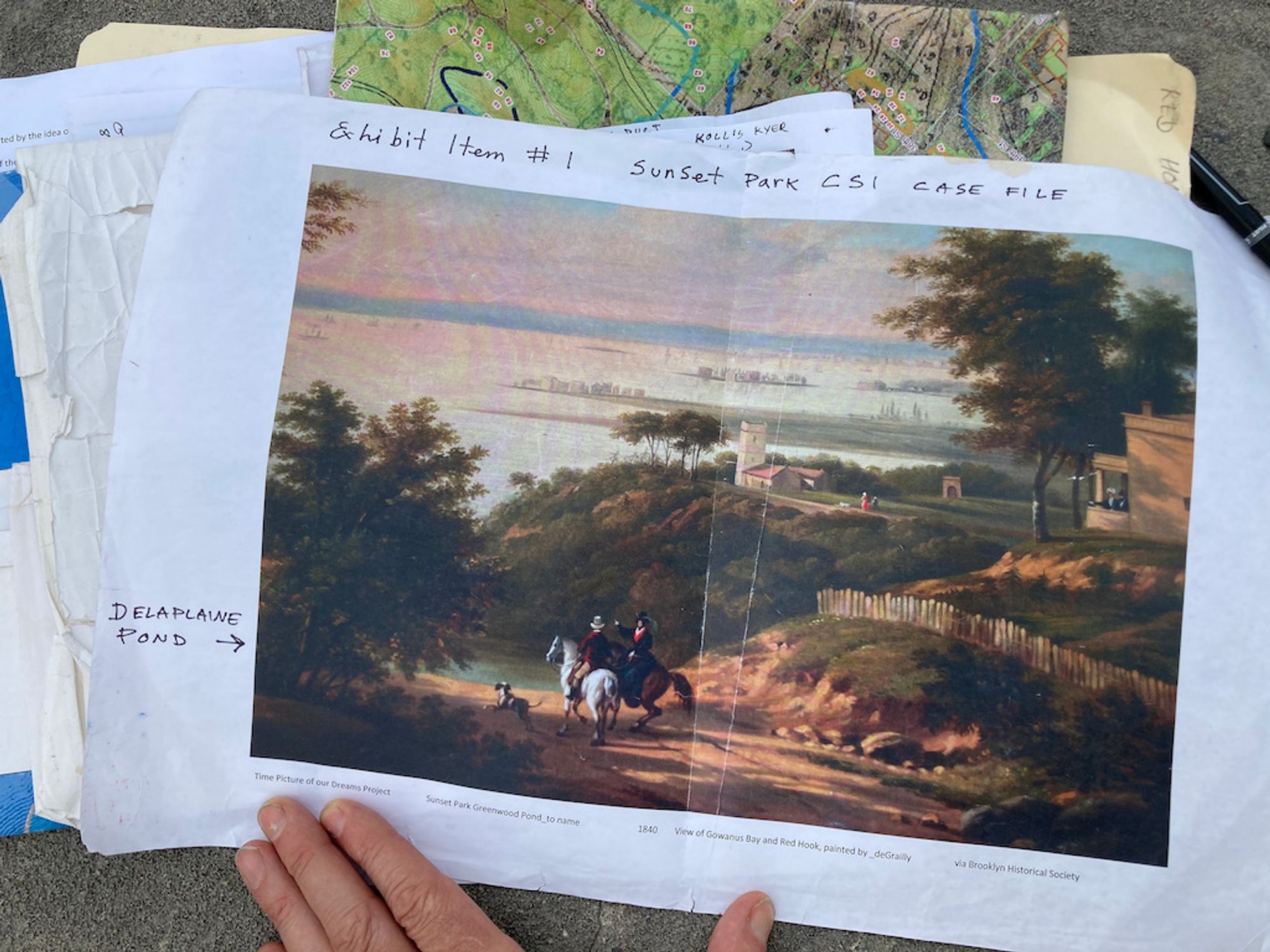

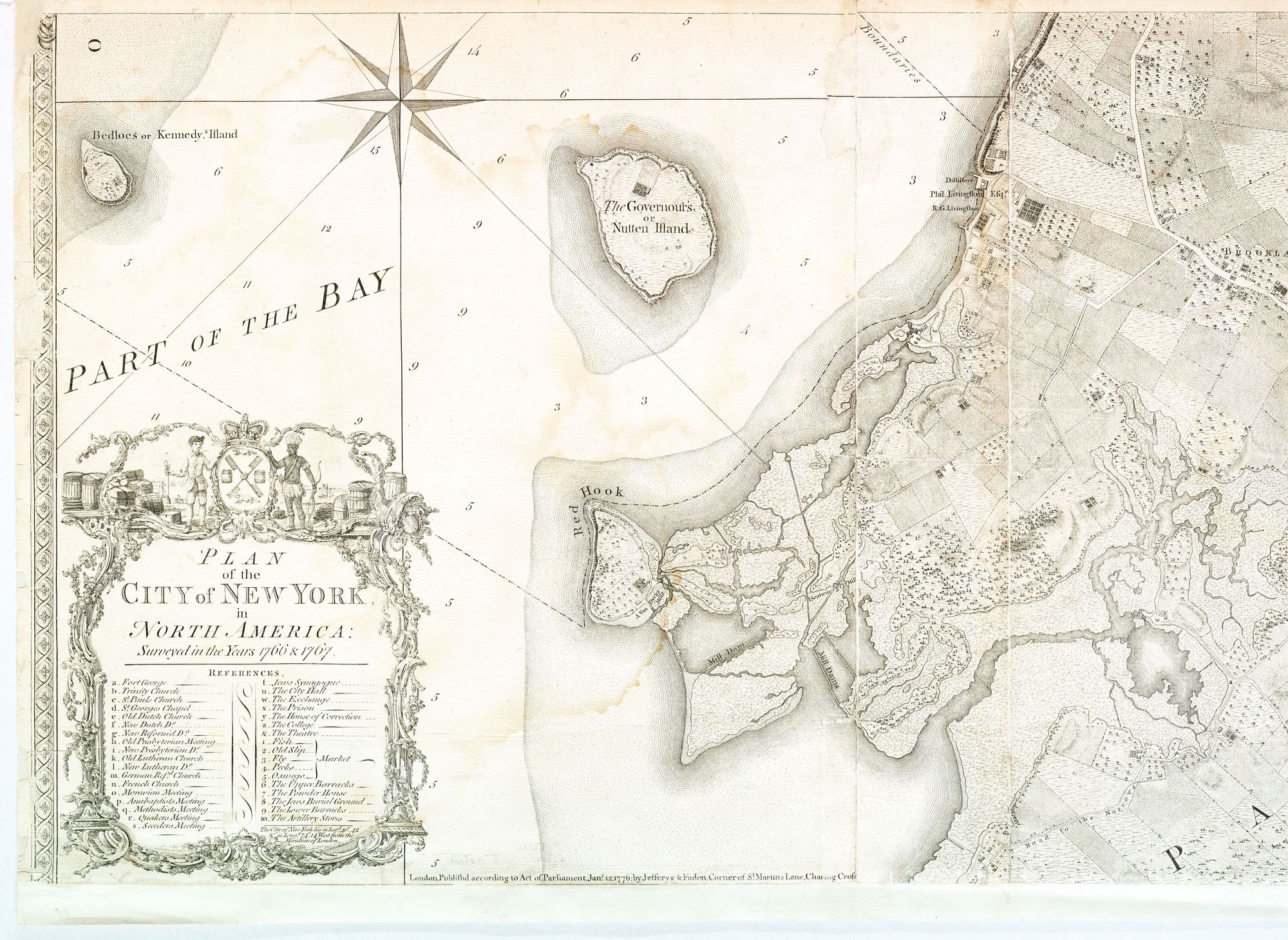

In the sheaf of papers Eymund has gathered for our mission, there’s a photocopied print of the “British Headquarters Map,” from 1782, which charts the area’s topography and streams in fine detail. (“The British in those days,” he explains, “made many precise maps of their colony—they were trying to put down a rebellion.”) There’s a landscape painting from the same era, composed from the vantage of the neighborhood we now call Sunset Park, which shows that the promontory the Dutch named “Roode Hoek” (Red Hook) was, in those days, in fact separated from the mainland by a stream. An etching of this same terrain, more close-in, shows that what the English dubbed Cypress Tree Island was once home to a mill where local worthy Isaac Seabring mashed ginger with alcohol to make elixirs, but whose notable feature—at least to Eymund—is a clump of bushy vegetation to the east of his ginger mill (“What’s that? An artesian spring!”). Another map, this one created by Eymund himself, is built from recent data on 311 calls: it charts where motorists and others are complaining of potholes. “I call this my map of curses,” he says. “The bigger the red dot, the more drivers yelling ‘fuck!’” (These are also places, he explains, where it’s likely there’s an old spring, or other watercourse under the pavement, that’s causing the road to buckle.) And then he unfolds our lodestar. It’s a composite map, also of Eymund’s own devising, that overlays another British-made chart of Red Hook’s waterways in the 1700s, this one by the famed cartographer Bernard Ratzer, with a precise current-day depiction of its modern streets and coast.

Eymund points, on this map, to the block of Pioneer Street where we’re now standing. It’s on the seaward side of Van Brunt—which is to say that we’re standing atop rubble dumped into the water by the same Irish laborers who flattened nearby Bergen Hill, in the 1840s, with pick-axes. The close-by intersection of Pioneer and Van Brunt, which once marked the waves’ edge, was also the mouth of an old stream the Dutch called Koeties Kill (Cow’s Stream). Its water now likely flows through a 12-inch clay pipe placed beneath Pioneer Street in the 1880s. But there’s a sure sign, Eymund says, that the springs that once fed the creek, at the edge of the moraine, are still bubbling up from the Long Island Aquifer. As we walk eastward on Pioneer toward Richards Street, he points to the low stoops of the tidy row-houses that line the block’s south side. Each of their stoops features protrusions of white PVC pipe that would be easy to miss if you weren’t looking for them, but which can only signal one thing. “Sump pumps,” Eymund says. “These homes’ basements fill with water for a reason.” Across the street, the dwellings facing them sit on ground that’s no higher; their stoops are naked.

Eymund points to the green expanse before us: Coffey Park. On his map from the 1700s, the park is blue. Before it was filled in 1895, this was a pond, as the wonderful website Red Hook Water Stories confirms, where neighborhood kids ice-skated in winter. The red brick towers of NYCHA’s Red Hook Houses, Eymund shows me on his map, sit on an erstwhile marsh that was used, before the city developed atop the resultant fill, as a dumping place for trash. But our first and main destination, on Dwight Street toward Otsego, is the biggest red dot on Eymund’s Map of Curses. “By the corner of Wolcott and Richards,” he says, “a lot of drivers are yelling ‘fuck!’”

Eymund notes the diagonal course of Otsego, as it courses past storefronts whose façades hawk US Fried Chicken & Pizza, or in the case of another called Alex Magic Touch Inc, haircuts. Most of Brooklyn’s streets were laid out in a cartesian grid during the 19th century. But laws protecting old rights-of-way mean that the presence of an odd triangle on today’s map often signals a road that predated the grid—and whose route, Eymund explains, usually had to do with water. In Manhattan, Broadway traverses Manhattan’s length on a diagonal because its route follows that of an old Indian path, the Wickquasgeck Trail, which traced the high ground between wetlands. And according to Eymund’s map, the reason that Otsego Street angles toward our destination on Wolcott here in Red Hook is plain: its course traces a part of a footpath first blazed by the Canarsie people, between what’s now Downtown Brooklyn and the Red Hook waterfront—a route known, in colonial days and for some time thereafter, as the Red Hook Trail.

There’s a new street-sign on a lamppost to mark this past: “Red Hook Heritage Trail.” The patrons and cats who abide by the other landmark on this corner, Tony’s Deli & Grocery, don’t seem to pay this sign much mind. But on the road in front of the bodega, it's not hard to clock from whence those 311 calls spring: on the asphalt is a deep depression. And a man fixing a car parked across the street confirms, when we ask him, that this sinkhole-like blemish is a recurring feature. “They keep filling the hole,” says Roberto Yulfo, standing by his black ’71 Mustang with a couple of its tires off. “But it keeps coming back.”

Yulfo wasn’t here in the days of the Red Hook Trail. But he has lived in the neighborhood, he tells me, since he came here in the 1980s from Aguadilla, Puerto Rico. And no doubt he’s seen a lot while tinkering with the Mustang which, he says, he’s parked across from Tony’s Deli for years. But I get the sense that even he's surprised by what Eymund does next. Looking at his map and down the street to ensure there’s no traffic coming, he crouches on the road, over a manhole cover embossed in iron with the letters “BPB.” (He’ll send me a link, later on, to what he says is another key resource in his C.S.I. toolkit: Designs Underfoot: The Art of Manhole Covers in New York City, by the photographer Diana Stuart.) Eymund puts his ear to a small hole in its surface, and nods. He calls me over to do the same. I crouch down. The sound is clear: rushing water. "That,“ he says, “is Ginger Mill Creek. 90-120 decibels, on a dry day like today—that’s an artesian flow.”

Roberto Yulfo, looking amused, says adios. Eymund explains to me, as we walk away, that there are countless places like this in the city—spots where he’s tried to convince the D.O.T. that repeatedly patching the pavement, without addressing the recurrent presence of water underneath, is folly. Pointing to a giant pump station installed a block away after Hurricane Sandy soaked the neighborhood in 2012, he also tells me that, as glad as he is for the measures that have been taken to mitigate the severity of future flooding, they are misguided. “During Sandy, flooding was actually much less of a problem than ponding—the inability of storm-water, once it was here, to drain to where it needed to go.” Gravity, after all, is free. And much of Eymund’s current work and advocacy involves convincing the city and private property-owners to help water go where it wants.

We walk east on Wolcott toward where the old waters of Ginger Mill Creek should debouche into the Buttermilk Channel, if Eymund’s chart of the storm drains is right. He pauses near the corner of Dikeman and Van Brunt––the spot where that clump of flora, in the etching of old Seabring’s mill, signaled a potent spring. Where Dikeman crosses Conover, just down from a big sign touting Steve’s Key Lime Pie, he points to the street’s mottled surface and quotes Sherlock Holmes: “the carpet is slightly crumpled where the body was dragged.” Whether or not the watery “body” dragged here belonged to that spring, he points to how the street’s cobble-stoned carpet was once plainly patched: most of the cobbles here are rectangles of Belgian granite—stones commonly used as ballast in ships during the 19th century and which later came to line many of New York’s streets. There’s also a stretch paved in smaller pieces, arrayed in the fan-like shapes that were the telltale method of the Portuguese craftsmen who resurfaced many of those streets, perhaps in the 1920s. Even the trees here, to Eymund’s eyes, evokes history’s layers. A tall flowering tree, in a vacant lot, signals a steady fresh water source underground, but also—given its genus and blooms—something else: “Anywhere you see an Empress of Pauwlonia, you’re seeing an outgrowth of the old Dutch trade in China—the tree’s seeds made it here from Asia because their dried pods are what the Dutch used to pack ceramics.”

It only makes sense, as we confirm on Eymund’s map, that this particular Empress of Polonia stands by what was once the water’s edge: the blocks between here and where ferries now dock in the Atlantic Basin feature no trees at all. They were long home to handsome old warehouses; now they’re filling with uglier, new ones––the “last mile” outposts of Amazon and DHL. “Can you feel, out here, how the vibe’s totally different? Asphalt is the sea of today.” He tells me, as we walk along Wolcott toward the water, that the fill here—the fill on which Pioneer Works is also built—isn’t just dirt and stone: that those Irish laborers who carted the remnants of Bergen Hill here also reported finding, in the rubble, bones from mastodons and other ancient fauna.

Am I surprised, there at Red Hook’s windswept edge, to see, beyond the chain-link fence that blocks the water, a lonely hydrant above what looks like a spout disbursing a steady stream? I’m not. And nor am I shocked when, that evening, Eymund sends me a satellite photo to prove his thesis: the smudge of smoke-like sediment emerging from Wolcott’s end into the Channel, in a time-lapsed image Eymund has tinted to show its outflow’s presence. It recalls the fan-like shape of those cobblestones on Dikeman. Traces of the body—or of Ginger Mill Creek, anyway—indeed. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast