Diaspora at a Distance

“Your whisper: exile is hard

let me into your mouth, let me blossom”

- Meena Alexander

How do we see a place that we have never been? How do we feel that which we have not directly experienced? How do we love those we’ve never known? What are we to make of such feelings, such sights, such love, across time? “Exile is predicated on the existence of, love for, and bond with, one’s native place,” writes Edward Said. “What is true of all exile is not that home and love of home are lost, but that loss is inherent in the very existence of

And what might we make of distance? Many things. We call our relatives “distant” for one—bound together by name and origin, though we may never meet. I feel distant from my motherland and distant from my own country all the same.

“Dear Shahid,” opens Kashmiri American writer Agha Shahid Ali’s poem, “I am writing to you from your far-off country. Far even from those of us who live here, where you no longer Written as a fictional letter from the perspective of a stranger who found a piece of mail addressed to the poet on the floor amongst thousands of other undelivered pieces of mail, Shahid charts in this prose poem the daily struggles of his people in occupied Kashmir. Eventually, the mail is returned to Shahid in the hopes it’s from someone he’s “longing for news from.” Inspired by the various modes of address in Shahid’s poem, I excerpted sections of “Dear Shahid,” as recited at a “die-in” protest by students at the Jamia Millia Islamia University (JMI) in 2017, in my film Letter From Your Far-Off Country (2020). Knowing what would come just two years later, when in 2019 India dissolved the Kashmiri constitution and shut off access to transportation, water, and contact with the outside world, and before police brutalized students at JMI for protesting, this “die-in” reading of “Dear Shahid” held much more weight. In the film, my father reads aloud a letter I wrote to a distant relative named Prabhakar Sanzgiri, an author, Communist party leader, and trade union activist in India, who passed away in 2011. In An Accented Cinema, Hamid Naficy writes of this intrinsic relationship between exile and the epistolary format: “[they] necessitate one another, for distance and absence drive them

What does it take for one to no longer recognize one’s country? For writer, theorist, and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha, the whole world is like a foreign land—a sense of estrangement can be a gift of insight that upends the very notion of We become fixed in our ways of knowing (and being known) when we settle.

To be unsettled is not to unsettle of course, for unsettling on occupied or stolen land asks the metaphysically impossible, according to writer, artist, and filmmaker Tiffany Sia: “How can you undo The project of decolonization has never been about going back in time or returning to some past untouched by colonization. Even Aimé Césaire refuted claims that he was “a prophet of the return to the pre-European Decolonization, one might formulate, is about building new worlds, not escaping back into old ones.

Despite this, historian Vikram Sampath—biographer of the far-right nationalist V.D. Savarkar (who was the inventor of the violent Hindu nationalist ideology Hindutva and an alleged co-conspirator of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948)—penned an essay in 2021 urging historians to “reclaim” Indian history from “leftist” historiography and the “stranglehold” of Subaltern, Marxist, and postmodernist Sampath argues historians must “decolonize” India’s history by recovering Hinduism’s ancient glory, and “heal” from the brutality of so-called “Islamic conquests” nearly a thousand years ago. Nevermind the current calls for Muslim genocide in present-day India from party leaders of the BJP, or the Hijab-ban in Karnataka schools, or the beatings that regularly occur out in the open, or the vandalizing of Mosques across the country during Ramadan 2022, or the bulldozing of Muslim homes. No, Sampath spills not one drop of ink on criticizing such brazen violence against Muslims. This false compression of difference into the Hindu/Muslim binary presents history as a distant past, something that one must “heal” from and “reckon” with, not as something alive, active, and lived through. History is weaponized by being kept at a distance. As Agha Shadid Ali writes, “your history gets in the way of my memory.”

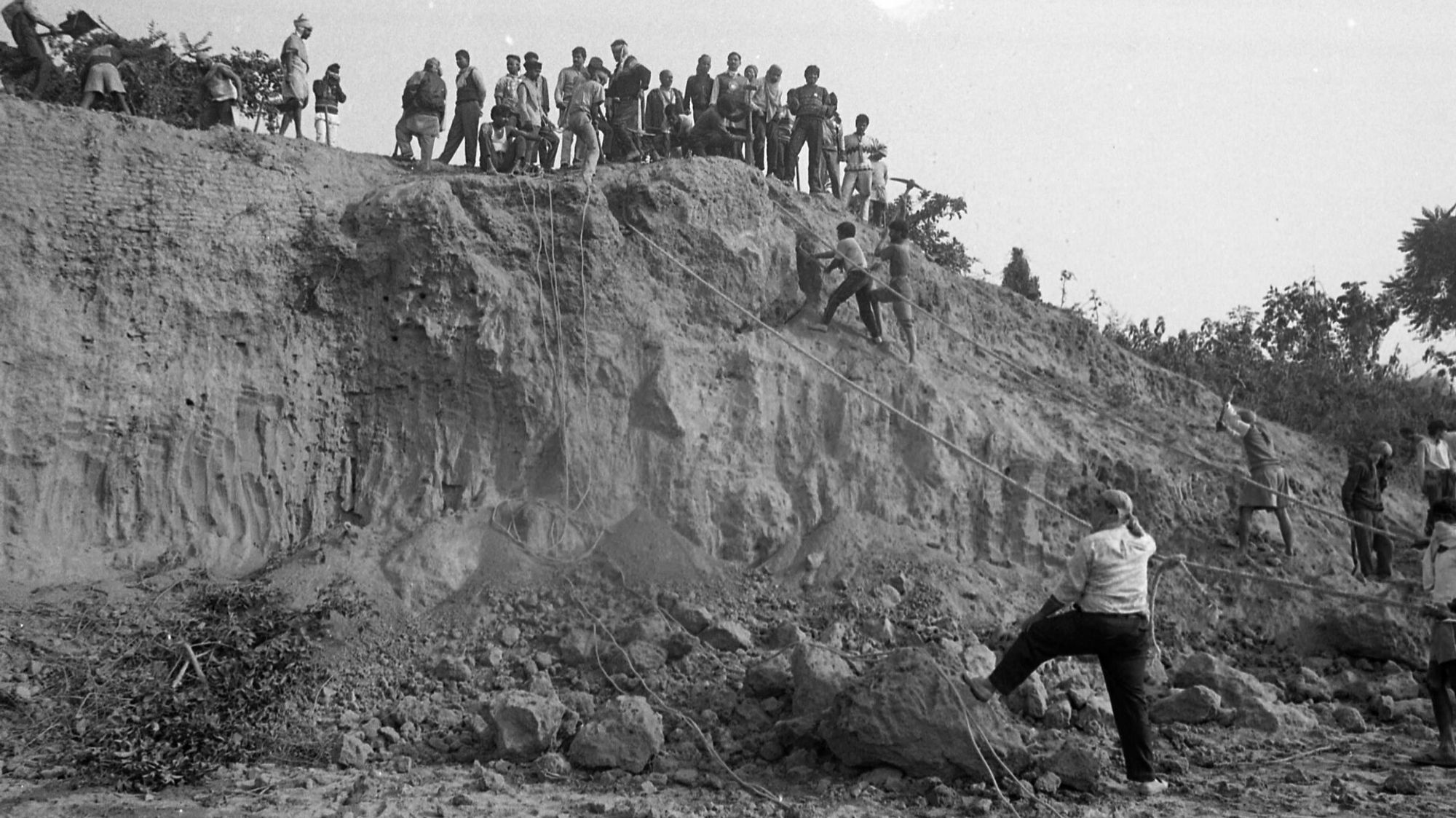

Sometimes, violently, time is undone. In 1992, Hindu extremists stormed the ancient Babri Masjid in the town of Ayodhya in India, reducing the mosque to rubble with their bare hands. The goal was clear: To return to some fictitious golden fantasy age of Hindu rule—in essence, an undoing of time toward a past that never was. Thousands were killed, the majority of whom were Muslim. Ripples of that moment echo with thunderous nationalist cries of Jai Shri Ram (Victory to Lord Ram) across the global diaspora to this day, “a cry for a cleansing so pure that all the complexities of a multitudinous, multireligious past are wiped out and history is remade in the apocalypse of the mind,” reflected poet Meena Alexander during a protest she attended in Connecticut after the events in Built in the sixteenth century on orders by emperor Babar of the Mughal Empire, the Babri Masjid is where Hindus have long claimed was the same birthplace of Lord Ram. Violent disputes over who the land should belong to have been ongoing since at least the eighteenth century.

“... You throw towards Babar all the stones

It is my head’s fault that, instead, it bleeds

Lord Ram had not even washed his feet in the Saryu waters

When he saw deep blots of blood.

Getting up without washing his feet in the waters

Lord Ram left the precincts of his own residence, bemoaning,

The state of my own capital no longer suits me

This December 6, I have been condemned to a second

In Kaifi Azmi’s Urdu poem Doosra Banwas (or The Second Exile), written one day after the demolition at the Babri Masjid and subsequent massacre, it was no longer just the citizens who couldn’t recognize their country anymore, but Lord Ram himself. Azmi, father of the actress Shabana Azmi, was cast as the ailing grandfather figure in Saeed Akhtar Mirza’s film Naseem (1995). “Why didn’t you choose to move to Pakistan?” asks Azmi’s son in the film, referring to the partition that left some two million dead and twenty million displaced. “Because your mother and I loved the tree in our backyard too much,” he responds. The film takes place in the days leading up to the fateful events of 1992 in Ayodhya. The violence is never directly shown however; we see the shock of the events through the family’s faces as they watch what unfolds on their television screen. Distance shields us from what we cannot bear to witness, and what we hope to never let others witness again.

All images are distant. We can hold them, touch them, see them, cherish them, but they are not of our place and time. That inherent disjuncture is a frighteningly painful (and sometimes beautiful) reminder, not of our mortality or finitude, but of the impossibility of being tethered to any time or any place. Images make exiles of us all.

Images are also dangerous. The crimes in Ayodhya were heavily photographed, despite many of the photographers being attacked by the VHP (Vishwa Hindu Parishad, or “World Hindu Association”) to seek out and destroy any evidence. According to veteran photojournalist Praveen Jain—whose photos five years prior led to the convictions of 16 members of the Uttar Pradesh police for their involvement in the killing of 42 Muslim youth—the VHP rehearsed the razing of the mosque the day before. Jain himself was invited by a VHP leader to witness the rehearsal of the crime—a baffling invitation. Jain photographed the event, but to his astonishment when he immediately returned to tell his fellow media personnel what he saw, no one believed him—not even his editor. The very next day, the Babri Masjid was demolished. Jain’s photos of the rehearsal would not be published until after the mosque was reduced to rubble. “Violence always makes an image of itself,” says theorist Jean-Luc Nancy, “violence always completes itself in the

After nearly three decades of deliberations, the court acquitted 32 BJP and VHP leaders of all charges on the basis of a “lack of evidence,” deciding the destruction of the Babri Masjid was “not pre-planned.” What then is the power of the image when it’s made impotent in the courts? What becomes of the power of witnessing if such images do not qualify as sufficient evidence? And what are we to make of the original invitation from the VHP to photograph the rehearsal of the demolition? Sometimes, ironically, violence invites visibility.

The BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) coalesced sometime in the 1980s to formulate the political wing of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), a Hindu supremacist paramilitary volunteer organization that started in 1927, drawing inspiration from both the Nazi party and the Italian fascist party. The RSS, which also had a hand in encouraging the massacre at Ayodhya, was officially banned in 1948 for its alleged involvement in Gandhi’s assassination, but was later found not responsible by the supreme court of India. Narendra Modi, India’s Prime Minister, has been a volunteer RSS member since the 1960s.

August 5th, 2020 marked the one-year anniversary of when the BJP (now the ruling party of India) invaded Kashmir, shut down their internet, transportation, and water, dissolved their constitution, replaced their flag, and arrested all their democratically elected officials. To mark this violent occasion, Hindutva supporters in New York, funded by the Indian American Public Affairs Committee (whose function is to fundraise for the BJP itself), rented a massive LED billboard in Times Square to celebrate the groundbreaking of a new Hindu temple, the Ram Mandir, on the grounds of the former Babri Masjid. I joined with a small handful of other protesters against this disgusting jingoistic display of propaganda in the name of our people, our diaspora. By the time we reached the protests, the billboard had been taken down from calls by a coalition of Muslim leaders, anti-fascists, and others. Clear Channel, the corporation that owns the billboard, issued a response, but Indian Twitter was already ablaze with Jai Shri Ram once more. The damage was done. Victory was claimed by Hindu supremacists. It was no longer I who had to travel thousands of miles away to India; India was now traveling to me via a burning saffron

Diaspora is not a collapsing of identity. It is a constant evolution, expansion, becoming and unfolding. It is unstable and fluid just as the slippery processes of chemical interaction with water that gives life to all analog State-based consolidation of identity is always a theft, a dispossession, towards the production of a nationalism that delineates between those who belong and those who do not. Diaspora is oceanic in its thinking, and state-based consolidation of identity is an arid landscape in ruins. Martinique-born philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant defines this violent filiation as “root identity,” claiming such formations are founded in “the distant past in a vision, a myth of the creation of the world,” and is “ratified by a claim to legitimacy that allows a community to proclaim its entitlement to the possession of a land which thus becomes a territory.” In contrast, Glissant offers a “relation identity” in its stead, “linked not to a creation of the world, but to the conscious and contradictory experience of contacts among cultures,” and, perhaps most importantly, “does not think of a land as a territory from which to project toward other territories but as a place where one gives-on-and-with rather than

I didn’t grow up in India, though I heard many stories of my father’s life there. Both my brothers spent time in India with my father’s family. After my parents separated when I was 8 years old, the possibility seemed foreclosed. In 2019, after finishing up my first short film in what would become a trilogy of works, I made the decision to finally visit my family and this distant motherland. I had only seen India through images taken through other people’s eyes. Had I kept India at a distance or had it been kept from me? At Home But Not At Home (2019) relied almost entirely on distant images—images that plagued me, haunted me, inspired me, but were not from me. Images that my father took, of my father himself, from India’s rich history of cinema, of Goa’s landscapes through Google walkthroughs and through commissioned drone videography, historical images of cross-continental solidarity, of decolonization.

How do we see a place that we have never touched? How do we feel that which we have not directly experienced? How do we love those we’ve never known? Did those questions finally fade as I stood on the beaches of my ancestors six months later, feeling the same warm breeze that they might have felt from the Arabian Sea? “Goa was to a large extent isolated from the rest of India for 400 years,” my father told me. Even my ancestral homeland was distant from itself it seemed.

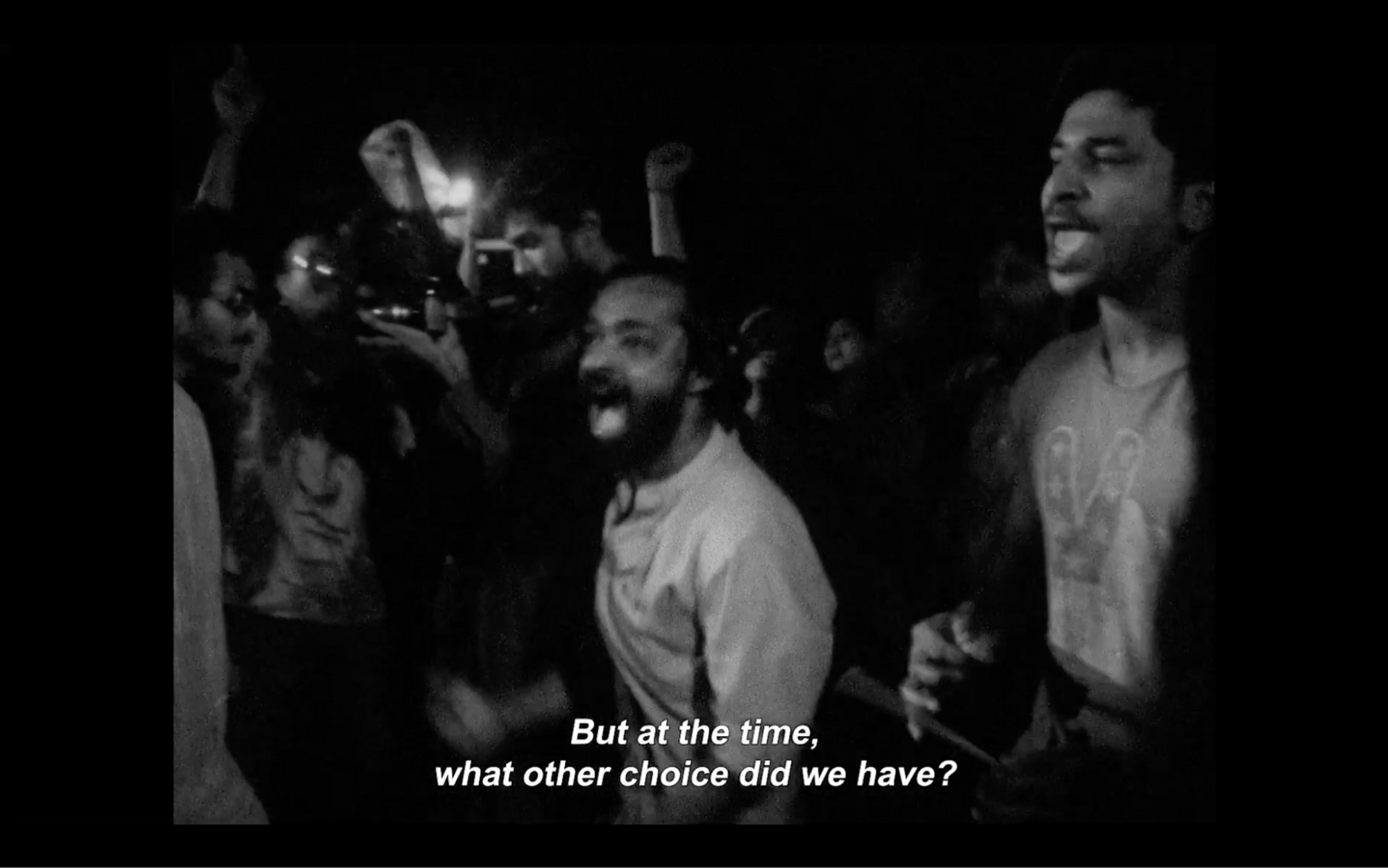

I started filming Letter From Your Far-Off Country quickly after arriving in Delhi in March 2020, just one week after an entire Muslim neighborhood was burned to the ground. Upon arrival, and at the encouragement of new friends in Delhi, I quickly joined the Shaheen Bagh protests—a spontaneous eruption of dissent against the new anti-Muslim Citizen Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Registration of Citizens (NRC) laws. I saw how the Shaheen Bagh movement—led primarily, and for one of the first times by Muslim women—intentionally wove the many threads between the struggle for the liberation of Dalits, Kashmiris, and Muslims in one tapestry. The protests were not unlike their Occupy-esque counterparts. Sit-ins lasted uninterrupted for months, hijras served free food to lines of neighboring people, and a “people’s library” filled with books in Hindi by Malcolm X and Angela Davis next to B.R. Ambedkar and Arundhati Roy. The movement spread quickly across the country, taking the name of the neighborhood where the sit-in protests first began, Shaheen Bagh. On the first day of the lockdown in March 2020, two days after I had narrowly escaped the grounding of all flights and left from my uncle and auntie’s home in Goa, Indian police swept the Shaheen Bagh camps, forcefully evicting and detaining the protesters. Cranes and tractors destroyed the main stage and tents, dismantling the art exhibits and hand-painted banners spreading messages of hope and resilience.

In the weeks leading up to my visit to India, the country was receiving international attention as images of the siege on the students of the Jamia Millia Islamia University spread fervently across social media. Students had for weeks been organizing against the CAA by staging marches and protesting. During one such demonstration on December 13th, 2019 students attempted to march to Parliament but were intercepted by the police, who attacked them with tear gas, stones and batons, arresting many students and injuring even more. That would not deter the protesters. Two days later, more than 2,000 students joined a massive protest against the CAA. That evening hundreds of police officers forcefully entered the JMI campus, violently attacking, rushing, and beating students with little hope of escape. Cell phone videos and CCTV footage of students being dragged and assaulted by police, and police throwing tear gas into the library while students were left scrambling were blasted all over news networks in India and widely across social media. Those images hit me with their distant force, an impact that struck with a velocity of thousands of miles at its back.

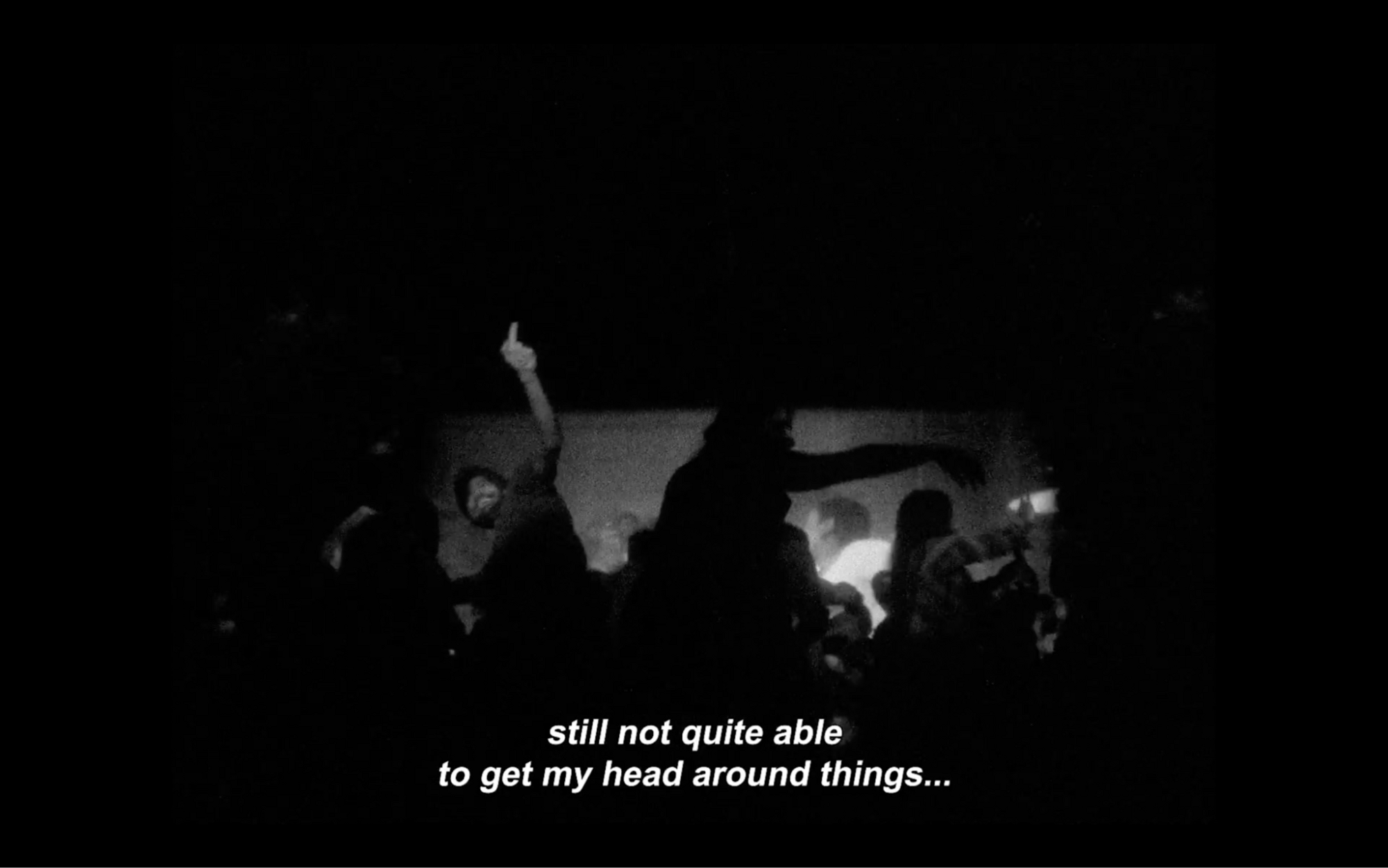

Payal Kapadia’s elegiac film A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021) traces the wreckage of the events at Jamia, following the build-up to the brutality in 2019 across student resistance in a multitude of forms dating back to 2015 when Kapadia herself was involved as a student in resistance efforts at the Film and Television Institute (FTII). Kapadia weaves an exchange of letters between lovers in an inter-caste relationship (which, as the opening titles tell us, were supposedly discovered in a cupboard at FTII) with intimate scenes of joy, terror, celebration, and stillness. A deep sense of uneasiness pervades the film, as narrators recount their dreams to one another. Kapadia unfolds these lovers’ lamentations into larger narratives of the sharp, fascistic turn of country, to deliberate what might be done about it—through cinema or otherwise. Writing on his notion of “exhilic filmmaking” Hamid Naficy states, “letters stand in for those who are absent and inaccessible. They are awaited with bated breath, cried over, kept close to the heart, shared with friends, protected, dreaded, mutilated, and destroyed [...] letters not only link people who are separated but also remind them of their

I remember leaving the theaters at the New York Film Festival, where I first caught it at the behest of nearly all of my friends (“You have to see this”). Completely silent, I was unable to join in the buzz of energy from others who were coming out of different theaters. A distance grew inside of me. I was unsure how to process the gravity of what I had seen. I was stunted by the same energy, rage, and sadness that filled me when I saw the same images of police brutality at Jamia nearly two years earlier, flung back into the fury that had created my own film Letter From Your Far-Off Country. Though our films share a lot in common, Kapadia ultimately did what I could not bring myself to do, adeptly inserting in her film CCTV footage of the military and paramilitary siege on Jamia in 2019. When does one find the courage to show what must be shown? When does one decide to conceal an atrocious image?

Susan Sontag, some 26 years after her seminal On Photography, reframed her original critique of images of violence and their inevitable tendency toward humanitarian impulses of empathy—an ever-present question of who gets to dispense that empathy and who is worthy to receive it—concludes, “let the atrocious image haunt us.”

“Cinema is the art of ghosts, a battle of phantoms,” French philosopher Jacques Derrida says in Ken McMullen’s improvisational film Ghost Dance (1983). “It’s the art of allowing ghosts to come back.” He continues, “I believe that ghosts are part of the future and that the modern technology of images like cinematography and telecommunication enhances the power of ghosts and their ability to haunt us.”

Let us not speak then of a past of distance, let us speak of a haunted future full of inhabited bodies, our graveyards full, so that the dead, the ghosts of exile, might speak for themselves, loudly, and with joy. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast